Introduction

Earlier this month the Labour government published a white paper on English devolution.

Perhaps fittingly for a White Paper released in December, the government invited turkeys to vote for Christmas. The government announced that it will invite proposals for two-tier areas (areas with a district council and a county council) to become unitary areas (areas with a single council), a process known as “unitarisation”.

“Unitarisation” has implications for local government finances and for local democracy.

As far as finances are concerned, unitary authorities are probably cheaper, but even if you believe PwC this depends on how many unitary authorities are created from each existing two-tier area.

The question as to whether unitarisation is good or bad for local democracy is harder to answer, and depends on some classic issues in democratic theory.

Take North Yorkshire unitary authority as an example. This new unitary authority has 90 councillors. There were formerly 229 district councillors serving this area together with 72 county councillors. Before there was one representative for roughly every two thousand people. Now there is one representative for roughly every seven thousand people.1

If you live in North Yorkshire, your elected representatives are metaphorically further away from you. Additionally, a majority in your former district council area might now be outvoted by representatives of other areas in the new combined area. I don’t know enough about intra-Yorkshire politics to say whether every other area will gang up on Richmondshire, but it seems possible.

These issues of access to elected representatives and the risk of becoming a minority within a larger decision-making unit are serious issues. That’s true whether we’re talking about English local government or qualified majority voting in the European Union. Opposition to unitarisation need not be a knee-jerk reaction.

At the same time, however, the degree of local democracy depends not just on the existence of formally democratic tiers, but on the powers that those tiers have and the recognition afforded them. The fact that some areas in England are “unparished areas” and some areas are “parished areas” is not seen as a great source of democratic inequality, because parish councils have limited powers and are not something people pay much attention to.

The White Paper – in what I can only describe as the gamification of local government reform – sets out a tiered set of extra powers that can be “unlocked” by councils at different levels. This might mean that some powers move from Westminster to local authorities. This might provide one response to the argument that unitarisation worsens local democracy. Another response comes from one potentially unforeseen consequence of unitarisation: the end of election by thirds.

Staggered elections

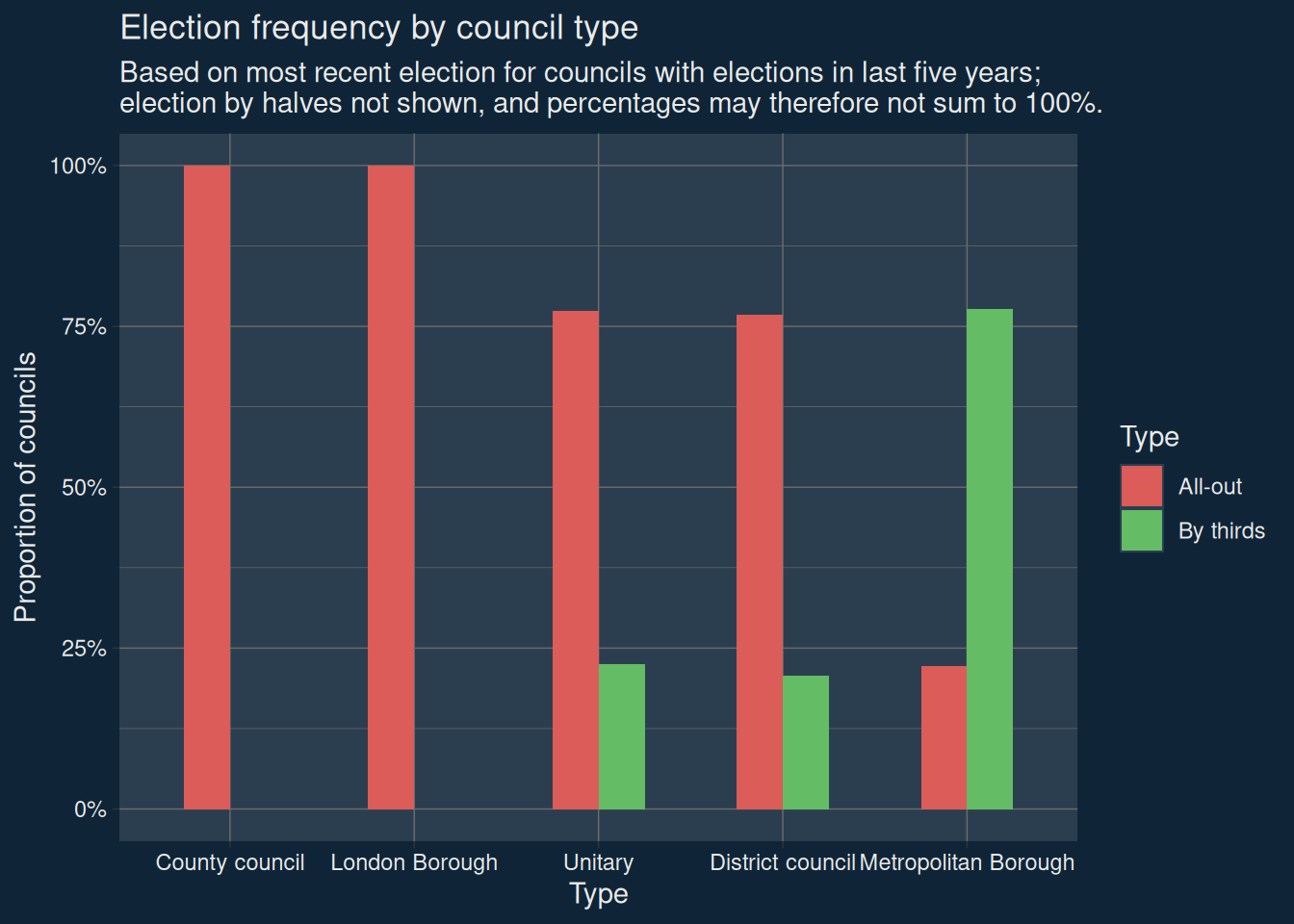

In just over a quarter of English councils, councillors are elected in staggered elections where (usually) one third of the council is elected every year, with the final year in a four year cycle seeing no elections.

Over the past twenty years, a number of councils have moved from staggered election by thirds to whole council or “all-out” elections. As far as I am aware, only one council has ever moved from whole council elections to election by thirds: in 2004, Castle Point in Essex made the switch, only to switch back this year.

Castle Point Council, in a consultation document inviting local residents’ views on switching to whole council elections, provided a list of reasons for and against the switch. One of the reasons in favour of switching was that

“The results from whole-council elections are simpler and more easily understood by the electorate. This may increase turn-out at local elections.” (emphasis added)

Governments and politicians don’t always internalize the lessons of political science research, but this view is supported by research on the frequency of elections and turnout.

- Filip Kostelka, Eva Krejcova, Nicolas Sauger and Alexander Wuttke) have shown that turnout in the general election of 2017 was lower in areas which had held local elections five weeks previously. This finding backs up their main finding (based on cross-national panel data) that the number of elections in a five year window is negatively associated with turnout.

- Colin Rallings, Michael Thrasher and Galina Borisyuk have shown that turnout in local authority by-elections is lower the less time has elapsed since the main council elections

Rallings, Thrasher and Borisyuk in particular treat the frequency of irregular by-elections as an illustration of a general point:

“One piece of evidence from British elections is the relative level of electoral turnout in the 32 London boroughs, which have whole council elections every four years, compared with that in the 36 metropolitan boroughs covering the major English conurbations outside London, which elect a third of their council membership annually. The two types of authority are responsible for the same local services, but the level of turnout is consistently higher in London. However, when general election turnout is examined the reverse position applies, with participation consistently higher in the metropolitan boroughs… A crucial factor in explaining these differences is likely to be that electors in the London boroughs are determining the composition of their council whereas their counterparts in the metropolitan boroughs will often be unable to effect a change in control however they cast their votes. Nonetheless, we should not ignore the possibility that the greater frequency with which electors in the metropolitan boroughs are expected to vote may also be a contributory factor to the differences in turnout” (emphasis added)

This paragraph nicely illustrates the two ways in which staggered elections can cause changes in turnout: by reducing the stakes (only one third of the council is at play) and by increasing election frequency. Of course, when term length is fixed, then increasing election frequency necessarily means reducing the stakes, and so some questions about mechanisms are moot in the English local government context.

Staggered elections and unitarisation

Staggered elections are found in a variety of English councils. Where there are staggered elections, councillors are usually elected in thirds, but a couple of weirdo councils (hello Oxford!) elect by halves.

Staggered elections aren’t only found in district councils. In fact, it’s metropolitan boroughs which are the most frequent users of this election type.

However when district councils have unitarised, the resulting unitary authorities tend to adopt all-out elections. For example: although two former councils in the North Yorkshire unitary council area (Craven and Harrogate) were elected by thirds, the new unitary council is elected in an all-out election. Similarly in Cumberland, although Carlisle elected by thirds the unitary council is elected in all-out elections.

Unitarisation might therefore reduce the number of councils electing by thirds, because no one choosing a new electoral system from scratch now seems to choose election by thirds.2 Although the government’s broader plans might include incentives for metropolitan boroughs to move away from election by thirds, it is far easier to choose a system for a new institution than change a system for an existing institution. Unitarisation won’t eliminate election by thirds, but it will likely make it less common.

All-out elections and turnout

So far all I’ve shown you is that some district councils use staggered elections, and that there are good reasons from other political science studies to think that this damages turnout. Now I’m going to go one step beyond, and try and estimate how much moving to all-out elections could boost turnout, using data from English local elections.

The data I’m using mostly comes from successive editions of the Rallings/Thrasher Local Elections Handbook; more recent data comes from the Electoral Commission or the handbooks jointly produced by Rallings/Thrasher and the House of Commons library. The turnout figures here are “ballot box turnout figures”, which includes ballots which were rejected at the count. The data covers from the period from 1991 to 2023; I’m not aware of a good complete source for turnout in the 2024 local elections. You can download the data in CSV format here.

The data includes information on the type of election: whole, thirds, or halves. This applies to the current election, rather than the general scheme of elections used by that council. As a result, councils can have “whole council” elections for two reasons:

- they generally have whole council elections;

- they generally have staggered elections, but have had to hold whole council elections as a result of boundary changes

Whole council elections which were held just because of boundary changes are marked in the column whole_bc_redistr.

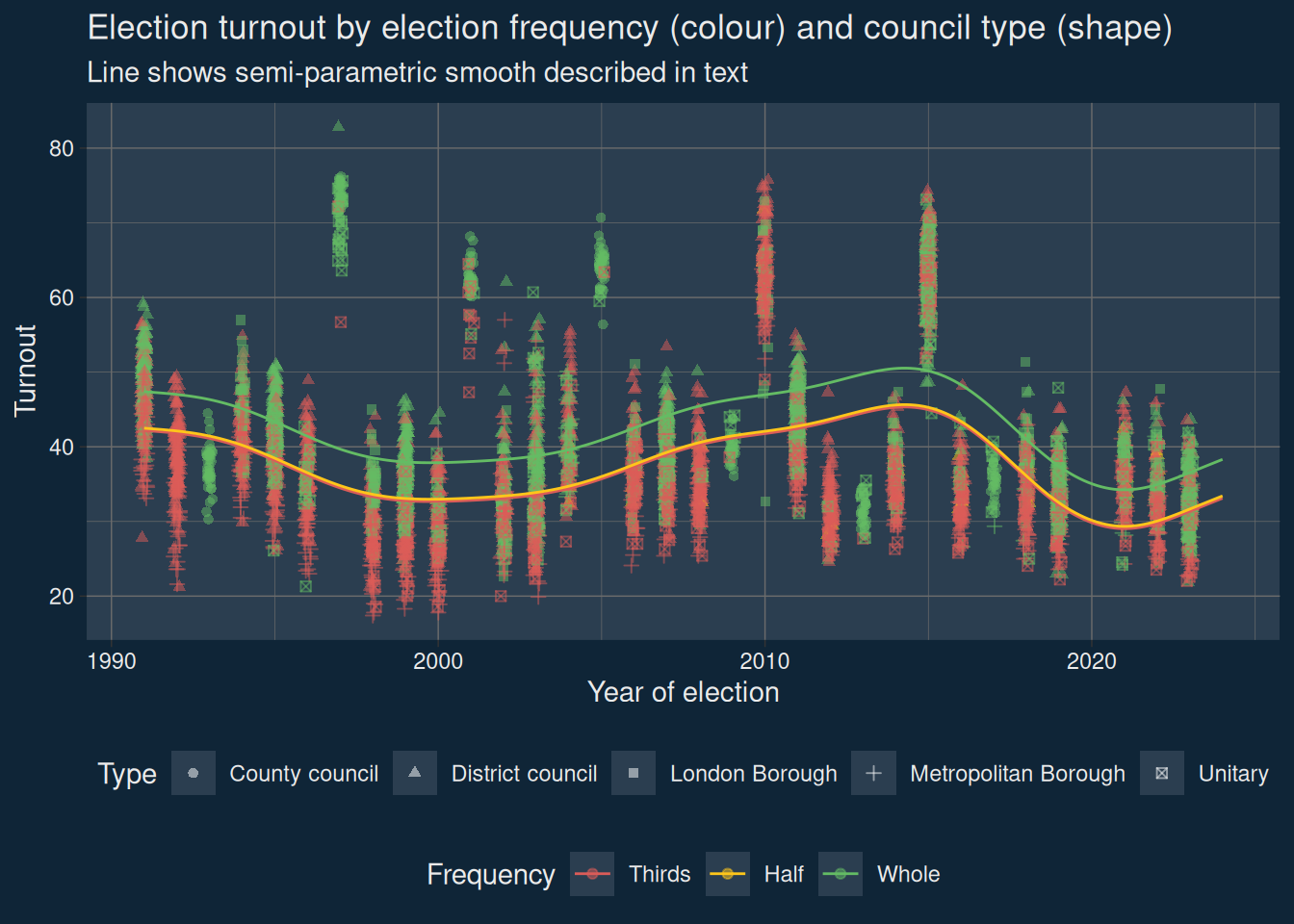

Figure 1 shows my attempt to plot the raw data. You’ll see peaks in election years (1997, 2001, 2005, 2010, and 2015). I’ve also overlaid three trend lines for the different election frequencies. These trend lines all share the same pattern over time, but they’re shifted up or down to best fit the pattern for the different election frequencies. The trend line for “whole council” elections is around four percentage points higher than the trend line for election by thirds. However, the higher turnout in these elections might be the result of the type of places which have these kinds of elections. What we really need are changes within councils.

We can estimate changes within councils by fitting a two-way fixed effects regression model. In TWFE models, we allow each year to affect turnout in its own unique way, and each unit (here, councils) to affect turnout in its own unique way. These year and unit fixed effects are nuisance parameters that we don’t really care about. What we do care about are the effects of other variables – in our case, the effects of election frequency.

If councils only ever held elections at the one frequency, then we wouldn’t be able to disentangle the council-specific effects from the effects of election frequency – but enough councils have changed election frequency over time to allow us to estimate some effects.

Any other things which might effect turnout – the presence of police and crime commissioner elections, concurrent European Parliament elections, postal vote trials, the changing quality of governance in the council – are either ignored or wrapped up into the year fixed effects.

| (0) | (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election by halves (v. thirds) | 0.978 | 0.284 | 0.269 | 0.609 |

| [−1.598, 3.554] | [−0.861, 1.429] | [−0.913, 1.451] | [−0.591, 1.808] | |

| All-out elections (v. thirds) | 4.644 | 1.296 | 0.864 | 0.901 |

| [4.069, 5.219] | [0.879, 1.712] | [0.193, 1.535] | [0.228, 1.574] | |

| Num.Obs. | 5337 | 5337 | 5131 | 5044 |

| R2 | 0.045 | 0.915 | 0.918 | 0.920 |

| Model (0) includes no controls. Model (1) includes year and council fixed effects. Model (2) is like model (1) but without all-out elections which required by redistricting. Model (3) is like model (2) but also excludes 2004 elections |

Table 1 shows the results of four different regression models of turnout in English local elections. The zero-th model includes no control variables at all, and just shows what was previously shown in Figure 1: that councils which hold all-out elections have turnout which is slightly moer than four points higher than councils which hold elections by-thirds.

Model (1) then goes on to include controls for year and the council. Under certain assumptions,3 we can now start speaking of the “effect” of all-out elections, compared to election by thirds. This first estimate of the effect suggests that moving to all out elections increases turnout by around 1.3 percentage points. This is quite a big effect. It’s around one quarter of the within-year standard deviation in turnout between councils. It’s also around the same size as the negative effect of general election turnout as a result of the new voter identification laws. However, since local election turnout is lower than general election turnout, the effect is proportionately bigger.

It’s true that the effect does drop a little bit when we drop some observations which we might think, for various reasons, to be problematic. Model (2) drops cases where a council held all-out elections required by redistricting. Our best estimate of the effect is now less than a percentage point. However, the difference between these two estimates isn’t itself significant: the confidence interval now runs between 0.2 percentage points and 1.5 percentage points, and so includes the point estimate from Model (1). When we drop turnout levels in 2004, which might have been affected by all-postal voting trials, the estimate goes back up a little, but by such a small amount relative to the degree of uncertainty that it’s really not worth reporting.

This suggests to me that moving to all-out elections would boost turnout, compared to election by thirds – and that if unitarisation involves getting rid of election by thirds then that might be something to be said in its favour.

Conclusion

Even people who think about local government reform probably don’t think first of its effects on turnout. However, someone probably should. For the last four years for which there is consistent data (2019 to 2023), turnout has been below fifty percent in every local authority area. I don’t know whether mission-led government is the same as government by target – but it would be nice to think of a mission to boost turnout. What would it take to bring turnout in local elections over fifty percent, what would that cost, and what trade-offs might be involved?

Footnotes

The population of the North Yorkshire unitary authority area is 623,501; this population divided by 229 + 72 is 2,071. The same population divided by 90 is 6,928.↩︎

@rogergiess.bsky.social points out that this was not true of an earlier wave of unitary authorities like Portsmouth, Thurrock and Reading which kept the district pattern of election by thirds.↩︎

That is, the usual assumptions for difference-in-difference analysis plus additional assumptions involving homogeneity of treatment effects and the absence of dynamic treatment effects required by the fact that we have staggered adoption and moves in and out of treatment. If you want to run the latest diff-in-diff estimator, be my guest. The difference between a blog post and an academic article, and it involves twenty pages of appendices and alternative estimators and data subsets.↩︎